The French Totally Withdrew From Indochina

In the end of 1955, the French totally withdrew from Indochina per the Geneva Accords. The Vietminh, however, stayed on in the border areas, using these areas as trails and hiding spots for their troops as part of an ultimate plan to invade South-Vietnam and unify the country of Vietnam. This was the main reason behind the US-Vietnam war during 1959-1975. Starting in 1955, the US sent many agents to provide assistance to the kingdom of Laos. The US observer in Xieng Khouang Province was Pop Buell, working for USAID.

In 1947, Phagna Touby Lyfoung got the high honor of being named the first Hmong Chaomuang (district chief) of Xieng Khouang Province, and Chong Toua Mua was named the first Hmong Naikong (semi-district chief) with administrative responsibilities over the Hmong in the Phou Dou area. That same year, Toulia Lyfoung was elected representative of Xieng Khouang Province, the very first one of Hmong ethnic origin. On May 11, 1947 Toulia Lyfoung was seated as a member of the National Assembly in the capital city of Vientiane. He later sponsored a legislation that established equal rights among all ethnic groups living in the kingdom of Laos.

During 1949-1958, Touby Lyfoung served as deputy-Governor of Xieng Khouang Province. At that time, the literacy rate for the Hmong living in urban areas was about 20 percent. Later on, Youa Pao Yang was promoted to the position of deputy-Governor in charge of the Hmong affairs, replacing Phagna Touby Lyfoung, and Txiaj Xab Mua was promoted to the position of Hmong district chief, replacing Youa Pao Yang. In 1949, Touby Ly foung decided to choose Youa Pao Yang to replace him as the Chaomuang Hmong. This made Beechou Lor unhappy and pushed him to join the Lao Issara, but in 1955 he came back to work for Touby Lyfoung. In 1961 Kong Le occupied Xieng Khouang, and Beechou joined Kong Le. In 1963, Beechou was assassined in the Plain of Jars by Kong La troops for unknown reason.

Photo # 22. Pop Buell from USAID diagnosed a sick child in Xieng Khouang in 1960.

Photo # 22. Pop Buell from USAID diagnosed a sick child in Xieng Khouang in 1960.

Photo #23. An old Thai Dam riffle

Photo #23. An old Thai Dam riffle

Photo #24. A Thai Khao woman working on her water-activated rice mill.

Photo #24. A Thai Khao woman working on her water-activated rice mill.

In June 1958, Touby Lyfoung got elected representative of Xieng Khouang Province at the complementary elections open to the Neo Lao Hatsat Party. After the elections, Touby then moved to Vientiane.

In 1949, Phagna Tougeu Lyfoung (see more details in Biography section) got married with Nang Sisamone Thammavong, the daughter of Nha Phor Thip Thammavong. (Mr. Thip Thammavong helped Gen. Vang Pao set up a joint Lao-Lao Hmong radio broadcasting program in Long Cheng, Military Region II. He later resettled in Canada and died in that country). In 1975, Tougeu Lyfoung and his family resettled in France. He later came to the USA where he died on February 10, 2004 of natural death.

Photo #25(left). Phagna Toulaprasith Tougeu Lyfoung

Photo #25(left). Phagna Toulaprasith Tougeu Lyfoung

Photo #26 (right). Tougeu Lyfoung and his wife Sisamone

Photo #26 (right). Tougeu Lyfoung and his wife Sisamone

Between 1750 and 1958, about 600,000 Hmong have resettled in the following provinces in northern Laos: Phongsaly, Luang Namtha, Luangprabang, Sayabouri, Houaphanh, Xieng Khouang, and Vientiane. [During that time, Bokeo was part of Luang Namtha Province, and Borikhamxay was part of Vientiane and Khammouane Provinces. As a result of territorial subdivisions made after the change of regime in 1975, Laos is now divided into 17 provinces, including Metropolitan-Vientiane, whose statute is a Prefecture]. As for the Hmong population in Xieng Khouang Province, the survey conducted by USAID in 1973 in territories under the Royal Government’s control revealed no less than 400,000 Hmong were living in that province.

On August 27, 1946 France signed a Modus Vivendis that granted the kingdom of Laos independence within the confine of the French Union. On July 19, 1949 France granted full independence to Laos’ King Sisavangvong while still providing financial support and assuming defense responsibilities vis-à-vis Laos’ neighboring countries.

China’s Policy Changes After WW-II

In 1949, changes in the political and administrative arenas that took place after the end of the Second World War led to serious conflicts between the democratic world and the socialist-communist world. Regime changes resulted in a world split in two blocks: a communist Eastern Block and a democratic Western block. Ho-Chi-Minh was given an opportunity to become a member of the Eastern bloc starting in 1950, as he needed logistic and military support and assistance from the other communist countries for his fight to expulse the French army from Vietnam and the entire Indochina peninsula.

Photo #27. – On July 19, 1949 King Sisavangvong signed the Treaty of “Independence within the French Union” with French President Vincent Auriol.

Photo #27. – On July 19, 1949 King Sisavangvong signed the Treaty of “Independence within the French Union” with French President Vincent Auriol.

In 1951, Communist China allowed Ho-Chi-Minh to mobilize his troops along the Chia-Vietnam and Vietnam-Laos borders to get ready for the fight against the French. In 1952, upon becoming aware of Ho-Chi-Minh’s plan, France initiated request for support and assistance from the US in preparation for a fight against Ho-Chi-Minh’s troops. With the same objective in mind, France also set up several military bases including Dien-Bien-Phu in North-Vietnam, Plain of Jars in Xieng Khouang Province, Xieng Ngeun in Louangprabang Province, and Seno in Savannakhet Province. The French wanted to be ready to fight against Ho-Chi-Minh’s army.

In December 1952, Ho Chi Minh sent Division 312 to attack Laos for the first time aiming at cutting French reserve forces in Houaphan and Phongsaly Provinces, and liberating those territories to serve as strongholds for the Lao Issara. At the same time, the Vietminh sent two of their regiments to Xieng Khouang Province with the following assignments:

– Regiment 148, moving from Samneua, to attack Ban Bane; and

– Regiment 195 (including Vietminh and Hmong Lor soldiers), moving from Muang Sene in central Vietnam, to attack Nonghet and use it a Hmong Lor military base.

Regiment 195 captured all the members of the Hmong Lee families and some of the Lao families as well, and detained them at Muang Sene, in central Vietnam. This detention created dissention within the Hmong community and caused them to split into two groups. From that point on, some sided with the Viet Minh, and others sided with the French.

Touby’s first wife died as a result of the Lor military invasion of Nonghet. May See Xiong was one of the captives that were detained for years in Muang Sene. She married Ly Doua about two months before the Lor’s attack on Nonghet and was taken prisoner. After she was released in 1955, she came back to live with her husband. She now resides in St. Paul, Minnesota. She said, “The hot climate in Muang Sene caused many of the women and children to catch malaria. They later spent their captivity in Sumou, at the Laos/North-Vietnam border”). The attack of Nonghet by the Lor and Viet Minh forced many Hmong to leave Nonghet for Lat Houang, Xieng Khouang, and Dong Dane.

Vietminh Division 308 headed to southern Laos, cleaned up French troops in Savannakhet and Saravane Provinces, and used jungles and mountainous sites in those provinces as military bases and training camps for the Viet-Cong from South-Vietnam, in preparation for the fights against South-Vietnam.

During August 13-15, 1950 Prince Souphanouvong announced his registration as a member of the Indochina Communist Party (Vietminh), apparently as an ignition cord to get the Vietminh involved in the armed fighting in Laos. He became the Trojan horse that helped the deployment of Vietminh troops into Laos. Not long afterwards, on August 20, 1953 the Lao Issara announced its political formation in the town of Samneua in preparation for the fight against the French and the Vientiane Royal Lao Government.

April 12, 1953 marked North-Vietnam’s second invasion of Laos. Army deployments included the following:

– Division 312 was to attack Louang Prabang and destroy the Xieng Ngeune airbase.

– Division 304 and Division 306 were to attack Xieng Khouang and Houaphan Provinces, including destroying the French airbase at the Plain of Jars.

– Division 308 was to attack SavannaKhet and destroy Seno airbase in central Laos.

Fighting in those areas occurred at the same time, but did not cause too many losses to the French troops. The main objective of the Vietminh attacks was to demoralize French, South-Vietnamese and Lao troops, and to immobilize troops that were about to be sent to reinforce Dien-Bien-Phu. The French had to counter-attack the Vietminh everywhere to keep them away from the various airbases, and ensure safe flights. Their troops operated on the highway from Xieng Khouang to Dien-Bien-Phu, from Louang Prabang to Houaphan and Dien-Bien-Phu, and from Louang Prabang to Nam Bak and Phongsaly. Because Dien-Bien-Phu was prematurely taken over by the Communists, the latter highway ended in the Nam Bak area.

Mr. Nouane Dam Inthivong, former civil servant in Houaphanh Province wrote, “As Dien Bien Phou was being encircled by the Vietminh and Communist China, the French ordered the Houaphanh Province civil and military officers to move to the Plain of Jars, Xieng Khouang Province, for safety reasons. Those evacues left on April 13, 1954, heading for the mountain range of Thieng Khay. On April 14, 1954 the North-Vietnamese communists caught up with them, arrested them at Ban Na Muang, and put them in prison at Phu Thieng Khay for around six months. Some of them were released on September 14, 1954.

The communists set up a people court to decide on the fate of the remaining detainees. On April 14, 1953 the following five people were sentenced to death at the First condemnation issued at Phu Thieng Khay:

- Mr. Khampane Bounyarith, Governor of Houaphanh Province;

- Mr. Xieng Khammy, Chaomuang of Xieng Kho;

- Mr. Phommasy, leader of village security guards in Samneua;

- Mr. Ba Boua, military officer stationed at Muang Pua; and

- Mr Ba Thong, military officer (and a native of Lat Bouak, Xieng Khouang Province).

On November 2, 1953 death sentences were issued at the Second condemnation at Ban Khang Khek, Muang Samneua, for:

1- Mr. Xieng Kanya Bounlutay, Chaomuang of Samtay;

2- Mr. Xiengthoune Bounlutay, deputy-Chaomuang of Samtai;

3- Lt. Kham Phieo, military officer stationed at Xieng Kho;

4- Mr. Bao Boua Heme Inthavong, Tasseng Pao of Muang Samtai;

5- Mr. Chanta, military officer stationed at Muang Phat Samtai;

6- Sergeant Xieng Gna, stationed at Ban Tao, Muang Samtai.

At the Third condemnation on November 03, 1954 at Kenglith Muang Kang and Muang Soy Houaphan Province, death sentences were issued for:

1- Mr. Ba Theng, Naikong of Muang Soy;

2- Mr. Pham Ba Theu, Chao Muang of Kaya (the father of Col. Khamtai So Phabmisay);

3- Lt. Lo Khamdao, military officer and interpretor stationed at the 23th Company of 8th Battalion BCL (the younger brother of Mr. Lo Khamthi Nokanya and the older brother of Lo Kham Dae or Nouane Dam Inthivong who wrote these notes); and

4- Mr. Khampha, Naiphong (Naikong) of Muang Kang at Muang Soy.

Finally, at the Fourth condemnation at an undisclosed site in the jungle, the following individuals were sentenced to death:

1- Mr. Oudom Phiphat, Chao Muang of Parkseng;

2- Mr. Phiakham, Tasseng of Muang Sone, Houaphanh Province;

3- Mr. Phengkeo, Naiphong of Sopsay;

4- Mr. Bathene, a French soldier stationed at Ban Xiengkhor;

5- Mr. Batoup, Naiban of Nongkieng;

6- Catholic Priest Rev. Thao Tieng, stationed at Muang Soy; and

7- Mr. Deo Van Peung, a French soldier stationed at Muang Seunela (a Thai Dam minority native).

Mr. Nouanedam Inthivong added that the Vietminh secretly executed thousands of people in Houaphan Province, and that they did everything to eradicate the Lao people with “no regret, no justice, and very inhumanely.” Their objective was to “kill the owner to get his property”, meaning the Lao territory.

Mr. Nouanedam now is a US citizen. (Thank you so much for giving this information).

After the Kong Le’s Coup d’état, the US reinforced the military camp of Nam Bak. Starting from 1962, Vietminh and Red China troops mounted ferocious attacks against this camp, causing great losses to the Royal Lao Army and causing more serious concerns to the US. President Eisenhower, who took office in 1953, used to declare, “If Laos were to fall, the door would be wide open for the Communists to invade the entire south-east Asia region.” This was the reason that convinced President Kennedy to send troops to set up defensive positions in Thailand in 1962.

An ex-military parachute jumper also noted in his memoirs that, by the end of April 1953, France sent two battalions of Lao and Lao Hmong soldiers for parachute training. The Lao contingent went to Seno, Savannakhet Province, and the Lao Hmong contingent went to Chinaimo, Vientiane Province.

In mid-April 1953, France had two divisions of French Foreign Legion troopers chasing the Vietminh away from the Plain of Jars as follows:

- One company of French Foreign Legion troops coming from Europe, together with South-Vietnamese soldiers, to cleanse the enemy along Highway 4 from the Plain of Jars, to Lat Houang, to Dong Dane, and liberate the town of Xieng Khouang and remain there until further order, and

- Another division of French Foreign Legion troops also coming from Europe, to cleanse the enemy along Highway 7 from the Plain of Jars, to Khang Khai, to Phou Dou, to Tat Peub Falls, and liberate Ban Bane and stay there until further order.

By the end of June 1953, two battalions of Lao and Lao Hmong troops who had just completed parachute jumping training returned to Xieng Khouang with the mission to cleanse the Vietminh troops at various sites within Xieng Khouang Province and be ready for deployment to reinforce Dien-Bien-Phu troops. The cleansing operations that started in June 1953 were performed by the following army units:

- One Lao Hmong battalion under the command of Sergeant Major Youava Lee, moving from the Plain of Jars heading toward Xieng Khouang to be combined with the French Foreign Legion troops stationed in the outskirt of Xieng Khouang. This battalion took the lead in the cleansing operation in the eastern region, between Xieng Khouang and Muang Mork, and all the way close to the border with Vietnam near the town of Muang Sene; and

- Two battalions of Lao and Lao Hmong parachute jumpers respectively under the command of Sergeant Major Deuane Sounnarath and Sergeant Major Nengchu Thao, and the overall command of Lt. Max Mesnier and assistant-commander Lt. Vang Pao. Other military assistants included Sergeant Emery and Sergeant Langlade. These two battalions started the Vietminh cleansing operation in the Phu Dou and San Tior area, and then joined forces with three battalions of Hmong local villagers-guards commandos already stationed at San Tior. Those three battalions were respectively under the command of Naikong Vakai Yang, Kongtong Paoly, and another Hmong Vang Naikong.

From San Tior, the two battalions of parachute jumpers did the Vietminh cleansing operation in the direction of Ban Bane as planned, in cooperation with the commander of the French Foreign Legion troops waiting at Ban Bane. Once they have reached Ban Bane, those two battalions attacked the Vietminh camp of Ban Phou Nong, where about one enemy battalion was stationed. The attack occurred in the morning, when the enemy was still unprepared, and last for several hours. We lost two soldiers, one Lao and one Hmong, and had two injured –one Lao and one Hmong, including Sergeant-Major Deuane Sounnarath. Damages suffered by the enemy were not known, because the two sides went their separate ways, but the enemy must have for sure suffered more damages than our troops — since they were caught unaware and they were fighting back from a lower elevation. Our troops retreated to Ban Bane for a one-week rest. The Hmong battalion then returned to San Tior, while the Lao battalion remained at Ban Bane because their commander had been injured.

Once they were back at San Tior, the Hmong battalion of parachute jumpers was merged with the three battalions of local villager guards under the overall command of Lt. Max Mesnier and Lt. Vang Pao. The combined battalions moved from San Tior to Ban Houei Kinin and got ambushed by the enemy at mid-way, resulting in the loss of two villager-guards and the death of five Vietminh soldiers. Our troops moved on and were able to read the enemy’s position, only a few kilometers away from Ban Houei Kinin. Lt. Vang Pao led a quiet attack without the enemy’s knowledge, killing 20 of them on the spot, injuring several troopers and forcing the rest to run away. Our troops suffered no casualties.

The reinforced battalions moved on toward the old village of Lor Blia Yao (the Kaitong) by the name of Ban Keng Khouay, and ran into some enemy resistance. The French commander ordered his troops to keep moving ahead toward Ban Phak Lak, where some fighting occurred with the enemy stationed at that village. Our troops stayed at Ban Phak Lak for a short while waiting for further order, and resupply of food and ammunitions, and head counts update. Once everything was ready, the troops moved out according to a secret plan, i.e., at first, moving toward Nonghet during the day time and then at night moving in a different direction –toward Ban Keo Patou, the village of Lt. Vang Pao’s father and the headquarters of Vietminh’s Regiment 195. Before positioning the troops for the attack, the French commander asked for time to allow for Sergeant-Major Youava Lee’s battalion to arrive. The plan of attack was based on the following deployments:

- Sergeant-Major Youava Lee’s battalion, combined with one battalion of Hmong Commandos, was to deploy from south to south-east toward Ban Keo Patou; and

- Lt. Vang Pao’s battalion of parachute jumpers, combined with one battalion of Hmong Commandos, was to deploy from southwest to north-east to Ban Keo Patou, with the overall mission to attack the enemy at Ban Keo Patou.

The fight was extremely furious, last for almost three hours, and resulted in the following results for our troops:

- Lt. Vang Pao’s battalion and the Commandos battalion: no losses;

- Sergeant-Major Youava Lee’s battalion: one soldier killed and another injured (Bliayao Xiong).

The Vietminh forces filled the whole village and paid little attention to the surrounding mountain range. The allied troops used that opportunity to occupy the mountain range and fought from those higher elevations. The enemy’s losses were uncertain, although the villagers later reported that these losses were quite heavy because the enemy was at a lower elevation and unprepared. The allies did not go in and verify the accuracy of the villagers’ report. Lt. Vang Pao pulled his troops for several days of rest at Ban Pha Boun and then moved them to Ban Phak Kherr to continue the cleansing operation in that region. At that point, the Vietminh changed their tactics. They then realized that the French were successful in using Hmong soldiers for guerilla fights, so the Vietminh started to use the same strategy –recruiting pro-Vietminh Hmong to serve in their guerilla units to fight against the French.

During September-October 1953, the fight against the Vietminh got more complicated as a result of this new Vietminh’s strategy of using their Hmong supporters (who were familiar with the area) as guides and informants. Between Phak Kherr and Nam Matt, the battalion of parachute jumpers recorded several fatalities when it was ambushed by the Vietminh. Naikong Mong Va, a very important leader in the Phak Kherr area and the commander of the Commandos troops, was one of the fatalities. The fight last for several days before fizzling out.

On November 16, 1953 the airborne battalion and three commando battalions were deployed to Nonghet. When they arrived at Ban Phou Nong Samchae, those troops (under the command of Lt. Mesnier and his deputy, Lt. Vang Pao) surrounded the village at around 4 a.m., took position at one of the mountains near the village, and got ready to attack Ban Nong Samcherr. The troops operating from the mountain did not pay attention to the other higher mountains located about one kilometer away. But Lt. Vang Pao led one company and headed toward the highest mountain around. As they were about to reach the top of that mountain, Lt. Vang Pao discovered fresh enemy footpaths that suggested new enemy maneuvers, and decided to wait until dawn to better identify the enemy’s positions. At dawn, the enemy shouted twice in Vietnamese and once in Hmong at the French troops on the lower mountain, “Are you guys over the hill friends or enemy?” They then fired at the troops on the lower mountain and inflicted several injuries to our soldiers.

When the Vietminh did the shouting, Lt. Vang Pao was not too far away from them, which allowed him to launch two BV bombs in their direction and caused them several fatalities and injuries. These were bombs that could be fired from special guns. One enemy soldier, who was seriously injured and could not run away, chose to hide in a cave near the high mountain and left behind a blood trail. Lt. Vang Pao ordered his nephew, Thong Vang, to go after the injured escapee.

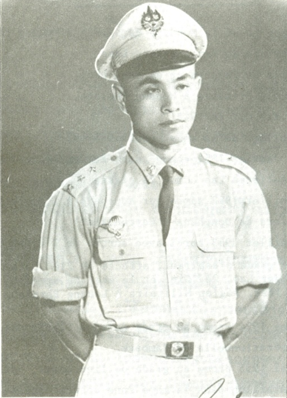

Photo #28 (left). Lt. Vang Pao standing in front of his nephew Thong Vang (with a white hat, died at Phou Nong Sam Cher on November 16, 1953).

Photo #28 (left). Lt. Vang Pao standing in front of his nephew Thong Vang (with a white hat, died at Phou Nong Sam Cher on November 16, 1953).

Photo #29 (right). The Hmong Commando Battalion that cleaned up the Viet-Minh in the Nong Het area in 1953.

Photo #29 (right). The Hmong Commando Battalion that cleaned up the Viet-Minh in the Nong Het area in 1953.

The latter was hiding in the cave, shot and killed Thong Vang on the spot. (Thong Vang was the soldier with a white cap shown walking behind Lt. Vang Pao on Photo #28). Sergeant-Major Emery tried to recover Thong Vang’s body but he too got seriously injured. Lt. Vang Pao tried to do the same. He fired at the escapee in the cave, who fired back and wounded him fairly bad. Two of Lt. Vang Pao’s soldiers tried to help him, but one got killed and the other one (Mua Cha) got seriously injured. The allied troops stopped the shooting until 4 or 5 p.m. before resuming it. At that point, they got no firing back from the enemy who must have escaped. Our troops then went in to haul out the bodies of dead soldiers and buried them after rituals.

In 1957 Laos was granted independence by France. The two sides had a chance to meet and talk. That’s how it was found out that the guy that shot Lt. Vang Pao was a Hmong native by the name of Seng Yang, a long time Vietminh recruit. He got hit by a BV bomb, fainted due to severe hemorrhage, could not flee and had no choice but to fight to death. Fortunately for him, the clouds were then all over the area, limiting the visibility range to 20 meters and allowing him to eventually escape.

After the attack of Ban Phou Samcherr, the airborne battalion and three commandos battalions went for a rest at Ban Pha Boun. Lt. Vang Pao went for an injury treatment, got promoted to the rank of Captain, and returned to his former Hmong regiment command position (where his marching order was still to cleanse the Vietminh from the North-Vietnam/Laos border area). This caused a lot of damages to the enemy because Capt. Vang Pao was using a different strategy – attacking at night, using trails the enemy was incapable to guess. This brought scores of good points for him that eventually reached Ho-Chi-Minh’s ears and prompted the Vietminh leader to say, “Vang Pao is a great fighter.” Indeed, Capt. Vang Pao was able to liberate several critical military posts, including

- Nam Kanh camp, an old military post that Chaomuang Tongpao Lee left in 1952 when the Lao Issara, the Vietminh and the Hmong Lor attacked Nonghet. This post was staunchly defended by the enemy but was still conquered by Capt. Vang Pao. (In 1977, North-Vietnam moved its border to the Nam Kanh camp, about 20 kilometers westward from the original border line). Ban Nong Khieo was an important village for the Hmong Lee (Naikong Vang Kailee’s village) that was attacked by the Hmong Lor and the Vietminh, forcing several thousands of Hmong living in that area to resettle at Lat Houang and in Xieng Khouang; and

- The eastern area of Nonghet, near the Laos/North-Vietnam border, close to Pak Kha (the village of Col. Lee Naokao Lyfong’s mother). After the Vietminh trail between Nonghet and Ban Keobone (the village of Kage Vang and Lt. Col. Vang Foung) was liberated, Capt. Vang Pao pulled his troops back to the French garrison of Nonghet.

Please read the book written by Lt. Col. David regarding the importance of the establishment and duty performance of the Lao and Lao Hmong military under the leadership of Phagna Touby Lyfoung and Chao Saykham Southakakoumane.

Absent those two leaders, the 1944-1945 military operation by the Ayrolles contingent would not have been possible, and Capt. Bichelot would not have been able to sustain the fight against the Japanese and the Vietminh troops. Later on, a new leadership was in place under Mr. Defarges (during 1950-1952) and Mr. Haze (during 1953-1954), who was well-known to many Hmong. Mr. Haze gave a jeep to Naikong Chongtoua Moua, who was the first Hmong who could drive a car. For lack of driving experience, the Naikong pulled the wrong shift-gear when he was driving uphill, forcing the jeep to move backward and roll into a small stream, seriously injuring himself. Mr. Haze sent him for medical treatment in Hanoi, North-Vietnam but he died on the way in. His body was brought back to Phou Dou for burial. This accident occurred in the beginning of 1952.

Duty Performance of Col. Mesnier

Mr. Mesnier was a special member of GCMA organization (Groupement de Commandos Mixtes Aeroportes – airborne Commandos). Following his graduation from the military cadet school in France, S/Lt. Mesnier was sent to duty in Indochina. In 1953, he was part of the GCMA operating in Saigon, South-Vietnam and, in July of the same year, was reassigned to Khang Khay, Xieng Khouang Province, to work with Capt. de Bazinde Bizons, the number one specialist in mountain gureilla warfare. S/Lt. Mesnier replaced Lt. Devaux at the commander of GCMA 201, which included 900 Hmong soldiers under Lt. Vang Pao and about 1,000 Lao soldiers. Sergeant-Major Deuane Sounnarath was the commander of the second Lao airborne battalion.

There were no less than 20 Lao and Lao Hmong officers, and two French officers, Sergeant Langlade and Sergeant Emery. Sergeant Emery got injured during the Phou Samcherr attack. The marching order for GCMA 201 was to cleanse the Vietminh in the Nonghet region, take over the Keo Patou region, and defend the Nonghet area, Xieng Khouang Province. Lt. Vang Pao and his Hmong subordinates were in charge of collecting news and monitoring the enemy movements. All this information was critical to the success of the enemy cleansing operation.

Photo #30. Col. Max Mesnier with his wife Francoise in France, May 8, 2008

Photo #30. Col. Max Mesnier with his wife Francoise in France, May 8, 2008

Photo #31. Lt. Max Mesnier in Laos, August 1954

Photo #31. Lt. Max Mesnier in Laos, August 1954

On November 16, 1953 a major fight against the enemy took place at the Nong Samcherr mountain range. At that time, Lt. Vang Pao was the operational commander, assisted by two French officers, Sergeants Emery and Langlade. The end results from the allies’ side included two dead soldiers and several injuries affecting Lt. Vang Pao, Sergeant Emery and two soldiers. The enemy lost 15 soldiers on the spot. The airborne battalion, the GCMA and the Marquis ceased all operations before the beginning of December 1953. Three medics landed on parachutes to administer chicken pox injections to the troopers, following the earlier deaths of several soldiers. From October 1953 to March 1954, the airborne battalion and the Marquis contingent attacked Viet-Ming Division 195 and Battalion 81 in the Nonghet area, and inflicted heavy losses to the enemy.

North-Vietnam Invaded Laos

(Please read the Agreement Kaysone signed with North-Vietnam).

In the last 10 years or so, Vietnam had a population of over 50 million people that were having hard time supporting themselves. The Vietnamese government then decided to invade several resourceful regions of Laos, especially the Boleven Plateau which was a rich agricultural region crossed by several streams. Fortunately for the Communist Vietnamese, luck was on their side in the form of faithful Lao followers that led to the signing of a Lao-Vietnam agreement which allowed no less than 5 million Vietnamese people to rush into Laos. Furthermore, the Communist Vietnamese also forced the Lao and the Lao Hmong from the Plain of Jars and the southern part of Laos to leave their lands and properties in an extremely painful and barbarous way, especially for the Lao Hmong. The lowland Lao were able to force themselves to live with the North-Vietnamese, although some of them had to move somewhere else.

Some of the Hmong took shelter in several mountain ranges and tried to survive very summarily. Over the last few decades, thousands of them had been killed in the battlefields and/or forced into jail. Even worse, the Lao red communist government had granted Lao citizenship to North-Vietnamese and let over two million of them legally live in Laos. Those new citizens have the same rights as the Lao natives, are under the control of the North-Vietnamese army, and pretend they are here to help the Red Lao fight against the Lao rightists who want their country back in their hands. This removes the need for the Lao communist government to have an army of its own because North-Vietnam is already taking care of all of Laos’s national defense needs. The only thing left for the Red Lao government to do is to maintain a police force and local surveillance teams consisting of villager recruits to watch for any misdeed committed by Lao natives –the real owners of the country. These government forces are only equipped with light firearms like AK’s weapons with limited firing range. Therefore, the management of the country, in the eyes of observers from around the world, has always been perceived as being grossly deficient in terms of human rights. Yet, no other countries in the world had stepped in to try to discourage such a practice. What they have done, if anything, was mostly to assist in other areas because the communists are very good at hiding their long-term goals.

In August 2004, the Vietnamese communist government claimed there are many deep jungles in Laos that serve as shelters for the anti-government forces. For this reason, they have sent teams to go out and clear up Lao forests, hauling away all species of trees that are of use for any purposes to their people. Forest destruction made Laos an empty and dry land. Starting in 2006, development projects in Laos helped confirm that communist Vietnam has taken over Laos, including the various Lao government agencies that have been infiltrated by North-Vietnamese informants. Vietnamese men and women who roam the streets to sell hand-carried merchandises, and Vietnamese contractors who bid for construction jobs are all communist spies and informants. As for the Lao communist police and security guards, they are just secret agents looking for news to pass on to the Vietnamese communists.

The Lao red government does not try very hard to lead its people. It would rather just let them live like beggars and often looking for jobs in the neighboring countries or waiting for money to be sent in from relatives living abroad to survive on a day by day basis. Young kids are without care-takers, and lack education; many of them are insubordinate and drug addicts. This is the result of a plan to eradicate the Lao people faster to leave room for the Vietnamese to fill. All of the above observations came from an educated individual who loves the Lao people and is eager to reveal the truth about things happening in Laos for the Lao readers. That person is none other than Col. Max Mesnier.

The French promoted Capt. Vang Pao to the rank to Major and, in March 1954, put him in charge of the airborne battalion and the three commando battalions that have been resting at the Khang Khay garrison for one month. By the end of April 1954, the French mobilized an army division under the command of Maj. Vang Pao, consisting of two Hmong airborne battalions, two Hmong commando battalions, three Lao battalions, two battalions of French Foreign Legion, and one combined Lao and Lao Hmong battalion from Louangprabang. The division moved from Lat Bouak, near Khang Khay, crossed the Nam Khan Khao River, and went past Bong Tha, Na Khang, and Samtai. It was close to reaching Phou Leui Mountain when Dien-Bien-Phu surrendered to communist North-Vietnam on May 7, 1954.

Before the Dien-Bien-Phu camp was established, President Dwight D. Eisenhower, who took office in the beginning of 1953, used to say, “If we lose Laos, it would be as if we open the door of south-east Asia and India to the Communists.” For that reason, the US and the French governments agreed to teach a lesson to the Communists, at a time when the Communists were expanding tremendously in Asia. But the US misread the meaning of the fight against North-Vietnam; it felt it was against its policy of not assisting any country or any party that is fighting another country in an attempt to colonize that country. For the US, taking part in the Vietnam War would mean helping France regain power in Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia, and making them French colonies again.

Based on that stand, the US tried to contact Ho-Chi-Minh to persuade him not to attack Dien-Bien-Phu, arranged a conference in Geneva, Switzerland and set the May 21, 1954 date for that meeting. But Ho-Chi-Minh and the rest of the communist world wanted to impose their military and political power; they seized this opportunity to attack and capture Dien-Bien-Phu before the scheduled date for the Geneva conference in an attempt to spread their influence across the entire world. The US let the French fight the communists by themselves, although many countries on the communists’ side were fighting against the French.

While the Vietminh were attacking the French garrison of Dien-Bien-Phu, Ho-Chi-Minh learned that Maj. Vang Pao was the commander of an army division consisting entirely of Hmong recruits on its way to reinforce the embattled French garrison. He was deeply concerned by this news and ordered his own troops to intensify their efforts to seize Dien-Bien-Phu before Maj. Vang Pao’s forces arrived.

The fall of Dien-Bien-Phu sent the word “Communist” resonating throughout the entire world. The US then realized that Ho-Chi-Minh was not trustworthy in the Indochina peace negotiations at the July 20, 1954 scheduled conference in Geneva. Thus, the US did not signed the agreement; only 13 other countries did.

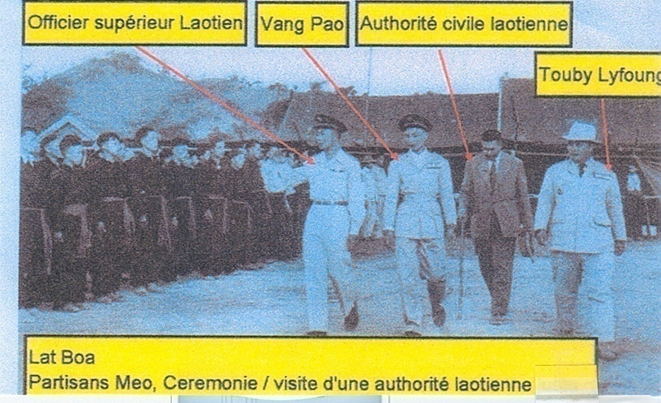

Photo #32. Lt. Col. Sang, Maj. Vang Pao, Chao Saykham Southakakoumane and Phagna Touby Lyfoung in Lat Bouak, west of Xieng Khouang in the end of April 1954, inspecting Hmong Commando troops ready for deployment to support French troops in Dien-Bien-Phu.

Photo #32. Lt. Col. Sang, Maj. Vang Pao, Chao Saykham Southakakoumane and Phagna Touby Lyfoung in Lat Bouak, west of Xieng Khouang in the end of April 1954, inspecting Hmong Commando troops ready for deployment to support French troops in Dien-Bien-Phu.

Photo #33. French Foreign Legion Troops under the command of Sgt. Leugeux.

Photo #33. French Foreign Legion Troops under the command of Sgt. Leugeux.

Photo #34. French Foreign Legion Troops under the command of Sgt. Paris.

Photo #34. French Foreign Legion Troops under the command of Sgt. Paris.

In 1954, Tou Lia Lyfoung came back for a break in Xieng Khouang in preparation for the next representative elections. He married for the second time with the adopted daughter of the Chaomuang Phuan in order to increase his popularity among the Xieng Khouang Province’s voters. Tou Lia was a noted personality, smart, and full of many good ideas to help his constituents. Instead of just staying relaxed, he tried hard to inspire many young Lao and Lao Hmong to attend training courses on family affairs and sanitation. The results of the courses were not as good as expected for lack of instructors and teaching materials.

In 1957, Tou Lia Lyfoung was invited to take another position in Vientiane as a member of a committee to review Laos’ legal matters. He stayed in Vientiane until the day he went to France as a political refugee. He passed away in France in 1996. While still living in Vientiane, Tou Lia took one of Lauj Faydang’s sons, Lauj Xauv, to live with him in 1958, when his protégé returned to Xieng Khouang and got married with Nang Say Her in Dong Dane. On May 18, 1959 Lauj Xauv and other Hmong Lor went back to Vietnam, refusing to be part of the Vientiane government.

Phagna Damrong Rithikay Touby Lyfoung (see his resume in Chapter 20) did not leave Laos because he had agreed with Prince Souvanna Phouma that they would stay together through thick and thin until the last day of their lives. However, Prince Souvanna Phouma has not been sent to jail like Touby was. Instead, he was able to stay peacefully at the house of his brother, Prince Souphanouvong, in Vientiane. Some believe that the two princes had supported the Neo Lao Haksat in delivering Laos on a golden plate to communist North-Vietnam. Because Prince Souvanna Phouma did not read between the lines, Laos ended up being divided into three parties that fight and self-destroyed each other. In the end, communist North-Vietnam came out the winner and was able to take Laos as a North-Vietnam’s colony.

In 1955, the two Lao political parties started negotiations on national unification. On June 10, 1956 the National Assembly met in a special session to discuss government restructuration and power sharing. During August 1-8, 1956 Prince Souphanouvong led his delegation to Vientiane to negotiate with the Vientiane faction. On November 2, 1957 the two parties signed an agreement to form the first two-party coalition government team on November 19, 1957.

The two parties agreed to have the Lao Communist regroup their troops as follows

- Dispatch one battalion consisting mostly of Hmong recruits to resettle in the Plain of Jars, Xieng Khouang Province (under the command of Lt. Col. Tou Ya);

- Dispatch one Lao Issara battalion to resettle in Samneua, Houaphan Province, and

- Allow several Lao Issara companies to serve in the capital city of Vientiane and the royal city of Louangprabang, and treating those two cities as neutral and unarmed centers.

In March 1958, the two sides started having some disagreements. The Pathet Lao were unhappy with their assigned role and refused to put the two provinces they have been controlling back under the control of the coalition government. There were too many things they did not trust. Therefore, King Savang Vatthana decided to ask Prince Souvanna Phouma to serve as Prime Minister with Prince Souphanouvong as his deputy. At any rate, political conflicts still continued to linger.

As a result of the 1957 political changes, Maj. Vang Pao was transferred to Muang Peunh, Houaphan Province to work on the defense of northern Laos. The communist party then agreed to be part of the new royal Lao government. In 1959, Gen. Phoumi Nosavan ordered the transfer of Maj. Vang Pao back to Xieng Khouang. In the beginning of that year, Maj. Vang Pao had ordered Capt. Leepao to pursue the Lao Issara troops who had fled the Plain of Jars on April 18, 1959, when Maj. Vang Pao was under the direct command of Gen. Ouan Rattikoun. In 1960, many issues surfaced, prompting Gen. Phoumi Nosavan to name Maj. Vang Pao as commander of the battalion in charge of the airbase at the Plain of Jars. Two weeks after Kong Le staged his coup d’état in Vientiane, Maj. Vang Pao himself was the subject of an assassination attempt by his deputy, but he safely escaped.

In November 1957, Capt. Kong Le was named director of the Commandos training school at the Chi Nai Mo camp in Vientiane Province. He used that opportunity to meet with Prince Souphanouvong every night at the prince’s residence at Pak Passack on the Mekong River bank, off Khoun Bourom Avenue, Vientiane. This was reported on page 49 of the book on national heroes of the Lane Xang authored by Douangsay Louangphasy. The August 9, 1960 coup d’état and the jail escape of Prince Souphanouvong and his followers proved that Kong Le might have a planning role in those events, making the jail escape so easy. There were many other new developments piling up during that period, developments that needed to be clarified by Gen. Kong Le (or Capt. Kong Le). For example, since he was a supporter of Prince Souphanouvong, why did he later choose to fight against the Lao communists again? What caused the Plain of Jars to fall and what forced him to retreat to Muang Phann? And, after the fall of Muang Phann, why did he decide to move to Muang Soui and finally to Muang Kasy, Vientiane Province (where he did not stay very long)? After Kong Le went abroad, the only thing left from the Neutralist Party was a name. The Lao civilian, military and police officers, for the most part, were not aware of the communists’ strategy and, therefore, became easy victims.

Photo#35. The first Hmong Coalition in Xieng Khouang Province. Front row L to R: Touby Lyfoung; Fai Dang Lo; Thao Tou Yang; Lo Foung. Second row: Youa Pao Yang; Mr. Toui Tounalom (Dr Khammeung’s father), Mrs. Touby Lyfoung; Mrs. Fai Dang Lo; Mrs. Lo Foung; Mr. Txiaj Xang Mua Chao. Third Row: # 1 unknown, #2 unknown, # 3 Ly Doua (former nurse, died in Thailand), #4 Mr. Seuang Sourinthavong, #5 and #6 unknown, # 7 Ly Khoua Lyfoung, # 8 unknown. Fourth Row: #1 Mr. Bounmy Thiphavong (Col. Sisavath’s father), #2 unknown, #3 Nao Yeng Ly, #4 Thao Hong Saycocie (chief of post office in Xieng Khouang), #5 with a black hat Blong Ly, former nurse, #6 Mr. Siphanh Sihanath (Xieng Khouang treasurer). The rest of the people are unknown.

Photo#35. The first Hmong Coalition in Xieng Khouang Province. Front row L to R: Touby Lyfoung; Fai Dang Lo; Thao Tou Yang; Lo Foung. Second row: Youa Pao Yang; Mr. Toui Tounalom (Dr Khammeung’s father), Mrs. Touby Lyfoung; Mrs. Fai Dang Lo; Mrs. Lo Foung; Mr. Txiaj Xang Mua Chao. Third Row: # 1 unknown, #2 unknown, # 3 Ly Doua (former nurse, died in Thailand), #4 Mr. Seuang Sourinthavong, #5 and #6 unknown, # 7 Ly Khoua Lyfoung, # 8 unknown. Fourth Row: #1 Mr. Bounmy Thiphavong (Col. Sisavath’s father), #2 unknown, #3 Nao Yeng Ly, #4 Thao Hong Saycocie (chief of post office in Xieng Khouang), #5 with a black hat Blong Ly, former nurse, #6 Mr. Siphanh Sihanath (Xieng Khouang treasurer). The rest of the people are unknown.

In December 1957, one Pathet Lao battalion was stationed at the Plain of Jars, another one in Houaphan Province, 250 soldiers in the city of Vientiane and 250 soldiers in the city of Louangprabang. Starting in 1958, the two political parties were faced with many issues. The Lao communists complained that they had been ranked unfairly, that things were not implemented as agreed, and that there were too many game plays. On May 14, 1959 Gen. Ouan Rattikoun flew up to Xieng Khouang to try to resolve misunderstandings with the Pathet Lao at the Plain of Jars but he was stopped and asked a gun point not to meet with anybody. The General had to fly back to Vientiane and, on May 17, 1959 ordered three of his battalions to lay siege to the Plain of Jars camp occupied by Lt. Col. Tou Ya. On May 17, 1959 the Pathet Lao promised to collaborate with the Vientiane faction within the next 24 hours. Because of this promise, the Vientiane’s troops did not pay close attention to the surrounded Pathet Lao troops. On May 18, 1959 heavy rain fell on the ground at mid-night allowing the Pathet Lao Battalion to escape, unbeknownst to the Vientiane surrounders. The following day, Gen. Ouan ordered his troops to trail them to no avail. He then ordered Maj. Vang Pao to get Hmong troops in the pursuit.

The leader of the pursuing team was Capt. Leepao. His unit caught up with the fleeing Pathet Lao near Muang Mork and engaged in a fight in which the commander of Pathet Lao Battalion 2, Tou Ya, got shot in the leg. Capt. Leepao reported to Maj. Vang Pao that most of the Pathet Lao troops were teenagers and women. Maj. Vang Pao ordered Capt. Leepao to stop the attack and let the enemy walk away. As for the Pathet Lao battalion stationed in Samneua, they did not run away. About 100 soldiers of various ethnic groups dropped their guns and went home. The rest, over 300 lowland Lao recruits, were moved to Saravan Province by the Vientiane government, and regrouped as a new battalion without any further complications.

Photo # 36. Capt. Kong Le (Vientiane 1957) when he met Tiao Souphanouvong every evening at Pak Pasak Khounboulom Road.

Photo # 36. Capt. Kong Le (Vientiane 1957) when he met Tiao Souphanouvong every evening at Pak Pasak Khounboulom Road.

Photo #37. The first Coalition Government (Vientiane Party & Communist Party) 1957 Front left: Souvanna Phouma and right: Souphanouvong

Photo #37. The first Coalition Government (Vientiane Party & Communist Party) 1957 Front left: Souvanna Phouma and right: Souphanouvong

During this entire period, Tougeu Lyfoung, Toulia Lyfoung and Touby Lyfoung resided in Vientiane as members of the National Assembly. No big problems occurred, just minor ones if anything. The two factions kept talking to each other through the International Control Commission set up by the Indochina Peace Accord signed in Geneva in 1954.

Vietnam Was Divided Into Two Parts

In 1954, Vietnam was divided into two parts: North-Vietnam and South-Vietnam.

- North-Vietnam –the Democratic Republic of Vietnam—is a communist socialist regime led by Ho-Chi-Minh as President, with Hanoi as the capital city; and

- South-Vietnam –the Republic of Vietnam—is a democratic regime under Emperor Bao-Dai with Saigon as the capital city. (Currently, Saigon is named Ho-Chi-Minh City).

The dividing line was the 17th parallel between Vinh-Linh and Quang-Tri. In 1955, Ho-Chi-Minh had planned to fight to pull the two parts of Vietnam into one. This resulted in the invasion of Laos by the North-Vietnamese Army, who used the Lao Issara as a mask so they could use part of Laos as a trail to South-Vietnam for their fight to unite their country. They built a road on the Lao territory stretching from the 17th parallel to Saravan and Quanh-Tri to the Laos border with Cambodia, a road named Doan 559 or Ho-Chi-Minh Trail starting in 1959. They took over part of Laos’ eastern border, from north to south, and used it as hiding shelters and training camps for their troops. At present, the Vietnamese communists are occupying both the land along the borderline and the Ho-Chi-Minh Trail, and treating them as their rightful properties without giving anybody any chance to protest.

After Vietnam regained its independence from France, Emperor Bao-Dai announced his abdication from the throne, citing the fact that Vietnam still remained a French colony as before. He then went to meet with Ho-Chi-Minh, forcing the South-Vietnamese to elect Ngo-Dinh-Diem as President in his place. Emperor Bao-Dai did not feel safe living in Vietnam and, therefore, sought political refuge in France where he died on July 31, 1997 in Paris.

Following the communists’ defeat of the French at Dien-Bien-Phu on January 6, 1956 the Lao Issara changed their name to Pathet Lao.

In 1957, the two Lao factions started working together but ran into many issues causing the Royal Lao Government (headed by Phoui Sananikone) to arrest on May 25, 1959 key members of the Lao communist party. Those arrested and detained at the Police Camp of Phone Kheng in Vientiane included 1) Prince Souphanouvong, 2) Phoumi Vongvichit, 3) Nouhak Phoumsavanh, 4) Phoune Sipraseuth, 5) Sithon Kommadam, 6) Xiengma Khaikhamphithoune, 7) Meunh Somvichit, #8 Sisana Seusane, 9) Singkapo Sikhot Chounlamany, 10) Khamphay Boupha, 11) Phao Phommachan, 12) Bouasy Chareunsouk, 13) Khamphet Phommavan, 14) Somboun Vongmor Bounthan, 15) Phoukhao and 16) Mana. The reasons for the arrests were as follows:

- The presence of communists in the royal Lao government has led the US to cut their assistance to Laos;

- The communists refused to let their troops and the two provinces under their control have anything to do with the Vientiane government. In addition, the Pathet Lao military unit stationed at the Plain of Jars had vacated the camp and went into hiding.

These were the reasons cited by the Phoui Sananikone Government. Foreign embassies in Vientiane were concerned and unhappy about this development.

On October 29, 1959 King Sisavangvong passed away. The situation in Laos worsened as a result of many issues, including plots used by the Lao communists to assassinate rightist politicians, high-ranking officials, businessmen, and religious preachers. All these reasons raised concerns within the US government, who then sent in more observers and instructors to train Lao police and military. The training received by Kong Le’s Second Battalion of parachute jumpers was an example. Because of that training, nobody paid much attention to what Kong Le might be doing during that period. Besides, the royal Lao government was busy making funeral arrangements for the deceased king, and was too distracted to watch the political detainees as closely as it should. This gave those detainees a good opportunity to easily run away from prison at mid-night on May 23, 1960. Thongsy Khotvongsa, the military guard in charge of the prison surveillance, served as the lead person in the jail break.

When Prince Souphanouvong and his followers were still in detention, the Vietnamese communists sent an agent to try to contact Capt. Kong Le and the prison surveillance staff. At that time, Saly Vongkhamsao, a member of the Indochina Communist Party, was tasked with building a political base in the plain of Vientiane. Capt. Kong Le was the one that contacted Prince Souphanouvong and Saly Vongkhamsao to lay out a plan to help Prince Souphanouvong and his team run away from the jail and find a temporary hiding place in the Vientiane area. He was looking for the right opportunity, and shooting for the funerals of King Sisavangvong scheduled for August 1960. On August 9, 1960 Capt. Kong Le staged a coup d’état in Vientiane, allowing Prince Souphanouvong and his team to travel safely to Samneua.

After the Kong Le’s coup d’état, military fighting intensified day by day, not only in Laos but also in Vietnam. This created a lot of problems for the Lao people who suffered and got scared — something that has not happen very often before.

In 1954, the Indochina Peace Accord made it clear that foreign troops must leave Laos, and for France to fully implemented the Accord by withdrawing all of its troops. By contrast, the number of North-Vietnamese troops in Laos kept growing, in flagrant violation of the Accord. On the surface, this seemed to enhance the success of Prince Souvanna Phouma’s neutral government. In reality, the Khang Khay camp in Xieng Khouang Province was full of communist troops and embassies of communist countries, and not a single embassy of a free world country. Because of that situation, the US decided to step in and support Chao Boun Oum Nachampassack and Gen. Phoumi Nosavan, and South-Vietnam in order to prevent communist expansion into Southeast-Asia.

After Prince Souphanouvong was put in detention, national elections took place that provided the majority of representative seats to Tiao Somsanith’s party. Tiao Somsanith then replaced Phoui Sananikone as Prime Minister and named Gen. Phoumi Nosavan as deputy-Prime Minister and Minister of Defense. Gen. Phoumi Nosavan then created the department of national coordination to replace the multitude of overlapping departments in Vientiane with a single office. Gen. Siho Lanephouthakoun (then an Army Colonel) became director of the new department.

In 1959, complementary national elections were scheduled to fill holes caused by the lack of communist participation in the previous elections. Moua Chia Sang was a candidate who ran for election to become a representative of Xieng Khouang Province. On his way to Nonghet, he was shot and killed in the car he was driving at Ban Phak Kher, near Nonghet, Xieng Khouang Province in the beginning of Apil 1960.