On May 10, 1975 the situation in Military Region II (MR-II) and the entire Laos took turns for the worse in a scary and unprecedented fashion, following the US unilateral decision to drop their assistance to the Vientiane faction. This left Laos without any source of military support in their fight against the Lao communists, who were strongly supported by the North-Vietnamese using weapons and ammunitions received from the Soviet Union. As a result, the commander of MR-II decided to leave the area in order to prevent his people from being further punished and tortured by the Lao and Vietnamese communists. He did so because he did not see any other way out; everything looked blurry for him. Many other high-ranking military officers also fled to Thailand, leaving behind their troops, nieces and nephews, families and relatives, without any pre-planning activities.

Because of those intense developments, the US had to bring in C 130, C46 and C47 aircrafts to fly several Long Cheng trooper families out to the refugee camp of Nam Phong, Khone Kaeng Chanwath, Thailand. Those aircrafts were not able to carry everybody away, because not too many people were aware of that airlift option and the lead time was too short. Some of the would-be evacuees also lived some distance away from Long Cheng and could not come in within the allocated timeframe. The air evacuation started on May 11, 1975 and ended at 11 a.m. on May 14, 1975 because by then the enemy had already completely surrounded Long Cheng. Once the airlift ended, thousands of military and civilians and their families left Long Cheng for Vientiane by roads or forest trails, trying to cross the river to Thailand to join their leaders and other family members that had been transported to Thailand before.

Gen. Vang Pao and Jerry Daniels boarded a USAID aircraft at the top of the Pharassavang mountain range, flew out behind the last C130 flight, landed at Muang Cha (LS113) and then flew to Nam Phong on a Porter aircraft. By the end of May 1975, the communists closed the road between Vientiane and Long Cheng and many other roads, and set up check-points to prevent all movements within the area. A group of Hmong on their way to Vientiane were shot by the Lao communists when they were about to cross the bridge over Nam Lik River. Several of them were killed or injured.

Civilians retreated to Ban Sone Na Sou, looking for new trails that would lead them through the jungle to Thailand. The Lao communists did all they could to discourage their flights, including setting up road blocks or even killing some of the refugees. Despite all those threats, the flights to Thailand still continued unabated. By the end of May 1975, the refugee movement toward the Laos-Thailand borderline was so intense that it began to create serious problems for the Thai and the Lao governments who then decided to close the border between the two countries. The Thai government also decided to send the Vientiane high-ranking military officers and leaders who were seeking refuge in Thailand to a third country.

After the departure of the Vientiane leaders from Thailand, the influx of refugees from Laos to Thailand still continued without any changes. The Thai government had to set up centers to provide shelter to refugees from Laos, Cambodia and South-Vietnam at several locations including Nong Khay in Changwad Nane, Vinay, Phanom, and Napho. After closing the Nong Khay camp following repeated arsonist acts and several murder cases, the Thai government closed a few more refugee camp in the northern and southern parts of Thailand.

Photo #173. C130 aircfrats s began to pick up Gen. Vang Pao’s people from Long Cheng on May 11, 19

Photo # 174. The last C-130 flight out of Long Chieng at noon on May 14, 1975 brought a lot of tears from the Hmong people. The mountain in the background was Phou Prarasavang, the site of the royal resort. Gen. Vang Pao and Jerry Daniel flew out that same day..

Photo # 175. US C46 aircraft carrying Long Cheng people away in 1975. Photo courtesy Roger Va Geu.

Sad and Pitiful Life of MR-II Refugees to Thailand:

The Hmong refugees had to go through dangerous deep jungles and high mountain ranges, mostly during night-time in order to avoid Lao communists’ ambushes and gun shots. May Lo, the sister of Reverend Mang Her who now lives in Minnesota, once reported that she and sixty of her relatives spent weeks walking through the jungle before reaching Paksane, south of Vientiane, with the ultimate plan of crossing the Mekong River into Thailand. One morning, at dawn, they realized they were being completely surrounded by the Lao communists. Everybody was arrested. Each man had his hands tied to the back and all the men were tied together near a small but fairly deep creek, and then shot to death by the Lao Communists, with their dead bodies falling into the creek. The women and the children, on the other hand, were not tied but were bluntly hit on the back of the head with Ak47 butts and sent to die in the creek. As they were about to hit May Lo’s head, she grabbed her 4-year old daughter and pressed her body against her chest. After the mother was hit, both she and her daughter fell into the creek. The Lao communists then left the site. The daughter kept grabbing her mother all day and all night.

The following morning, she was still lying on her mother, crying, and watching her mother while sitting on top of cadavers infested with flies. Half a day later, the mother regained consciousness but had a big head-ache and saw plenty of small maggots around her whole body. She washed off the maggots and asked her daughter, “How many days was I dead?” The daughter said, “I am hungry and thirsty. I have not eaten anything for a long time.” She hugged her daughter and looked around to see if there were other survivors. Apparently, no one else had survived. She was convinced God had saved her life so she could come back and take care of her daughter. She then took her daughter out of the creek. By coincidence, three Hmong refugees were walking by. She asked for their permission to walk with them toward the Thai border that same night. She reached Thailand in mid-1976 and was admitted to the hospital at Nong Khay refugee camp.

[I had a chance to interview May Lo at a psychiatric hospital in Minnesota where she was being treated for off-and-on neurologic problems. She said that sometimes she did not know what she was doing, and often crossed the streets without asking herself first whether there were any running cars or not. Sometimes, she also thought about the circumstances that preceded her husband’s murder and cried without an end, caught in an extreme feeling of fear].

In addition to the mistreatments by the Lao communists, armed robberies were also frequent, perpetrated by Thai and Lao felons ready to carry out their crimes on the Hmong along both sides of the Mekong River and causing several deaths.

A Hmong once hired a Thai boat that operated like a fishing boat in the middle of the Mekong River from dawn to sunset. This was during the rainy month of June 1976, when he noticed more than 20 dead bodies floating down the river. He was told that floating dead bodies during 1975-1985 were frequent incidents. From 1985 onward, nobody knows how many of the same incidents were still happening.

The US claimed that refugees that left their country after 1982 were “economic” refugees –not “political” refugees. This was not entirely true because some refugees had very little control over when they could or could not leave, especially the military units that operated away from the front line and were surrounded for a long time by the enemy without any chance to escape. The worst part of the exodus was coming from the mountain ranges down to the flat areas. The Hmong were dreadful about getting mosquito bites and being infected with malaria. Many of them had also been exposed to Agent Orange through direct rainfall exposure or drinking contaminated stream waters. The Lao communists had killed the Hmong without any sign of regret by dropping bombs, spraying chemical yellow rain or Agent Orange powders over every forest where the Hmong were.

Two Hmong refugees who made it to Nong Khay reported that they have seen the body of a recently deceased Hmong woman with a one-year old child sitting on the body and still feeding on the dead woman’s breast, despite the fact that the body was already in an early decomposition stage. They wanted very much to help the baby but were afraid that if and when the baby cried, the enemy would be able to track them. Because of this exceedingly high risk, they were not able to do anything. This explained why Lao refugee families with babies used opium to put their kids to sleep before they walked past dangerous check-points, especially at night and along the Mekong River bank where the Lao communists were known to be watching the human traffic.

A Hmong Xyooj woman by the name of Nang Song, affected with insomnia and deep sadness, and unable to do or remember anything, was admitted to a psychiatric facility in Minnesota. After one week of treatment, she was able to sleep and eat a little. By coincidence, I was then working at the facility and had a chance to ask her about her past medical history. She told me that she left LS05 (Padong) by foot, walked through the forest up to Phoubia Mountain and down to Muang Omm and then past several other mountain ranges. After the two to three day walk from Muang Omm, her mother got sick and passed away. Next, her father died of malaria contracted through mosquito bites, leaving only her and a 12-year old sister. Nang Song, then 14 and a half, and her younger sister continued their journey in the company of other relatives. When they got close to the Phou Khao Khouai Mountain, they had to climb high mountain peaks and steep rocks –a very difficult and energy consuming exercise. Nobody but you can help yourself.

When they faced a 4 to 5 feet tall rock plate, she had her sister sit down so she could step on her sister’s shoulders and then climb the rock. Once she was up, she pulled her sister up. Unfortunately, both of them had fever. As she lowered her hands and attempted to pull her sister up, she was not strong enough to do so. Everybody else was gone and there was nobody else to help them. She had to keep her sister hanging on her hands for a full day. Her sister grabbed her hands until she died on the spot. When she noticed her sister’s hands were getting cold, she lowered her sister to the ground. Her sister did reach the ground but then did not move at all. She wanted to go down and help her, but realized she too was dead tired because of the fever and many days without food –just eating tree roots and leaves. After she swallowed some food and water (provided by other passing-by refugees) and had recovered some energy, she was able to sit up and continue her walk to safety. From that point on, each time she thought about her sister and her parents, she would become dizzy and fainted. These conditions have been affecting her for several years and pushed her to sign up at the hospital for treatment in 1985.

Regiment 28 stationed at Bouam Long (LS32) was under the command of Col. Cheu Pao Mua. An aircraft flew him in for a meeting and then flew him out to Thailand immediately, leaving all of his troopers behind. Later on, his troopers fled into the jungle. Many of them got ambushed, arrested, and killed barbarously. Some went in to surrender to the authorities and then completely disappeared from the scenery without anybody knowing much about their fate. According to those who survived, the people who surrendered were all killed, even when they were still very young.

The Bouam Long Camp was the MR-II front-line post located behind the enemy ranks, northwest of the Plain of Jars. The camp has been attacked many times by the Lao and Vietnamese communists without much success. Starting from 1961, the year the camp was created, the enemy had suffered very heavy losses each time they attacked the site. The camp was a deadly strategic site that pushed the Lao and Vietnamese communists to arrest and kill many Hmong, and to cry out loud that, “The Hmong have deeply buried black hearts that smell like rotten skirts. You can wash them as much you want, they will still smell bad.”

[This was to be expected, because the Vietnamese and Lao communists put the lives of the Hmong below those of domesticated animals; everybody had to fend for himself/herself. The Hmong did not invade communist countries; the Vietnamese communists were the ones that invaded the Hmong and the Lao territory. We all had to stand up and fight off the destruction of the Lao nation and the Lao territory that we loved, a land that used to be a peaceful place for us to live our lives since childhood. When we were invaded, when our happiness and our nation were destroyed, we all had to be ready to risk our lives to avoid complete destruction].

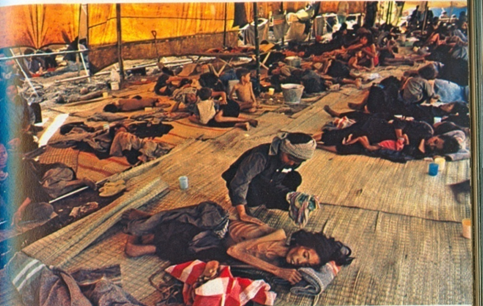

Photo #176. When refugees first arrived in the Camp in Thailand, many were sick and starving.

Hopeless Life In Refugee Camps

There are good and bad things in the refugee camps.

- The good things were that people had a shelter and a safe place to stay, without any life threat from the communists, in a place where there was enough to eat and to drink, and where people were under reasonably good cares from the Thai authorities from 1975 to 2006.

- The bad things were related to physical confinement. Refugees had to stay in the camp, with limited opportunities to go outside (unless accompanied by a Thai official). Our activities were restricted, without any hope for any personal training and development. Politics were the main deciding factor for the fate of the Lao refugees, because there was no certainty as to whether they would go back to their countries or have a chance to resettle later in Thailand or in a third country.

Because of all those uncertainties, many Lao refugees lived under intense emotional pressure, got very nervous, lost their memories, and lived a shorter life. These emotions caused some people to go to jail or even to die because they were too strong. During the behind-the-wall life in the Thai refugee camps, many had secretly escaped the camps to go and live with their Thai relatives, and ended up being stuck in Thailand and given no more chance to go to a third country for lack of T-numbers. Some of those who were lucky enough to be sent to a third country ran into health problems and died during their sleep. Several thousands of Lao refugees stayed behind in Thailand, and were later moved from Nam Phong-Soune Vinay camp to Soune Tham Kha-Bork camp to Soune Houei Nam Khao in 2009.

Luck had allowed many of the Lao refugees to see light during their dreams, as many countries in the world threw their helpful hands in our direction and allowed many of us to start a new life in their countries from 1976 until 2009. But there were also thousands of refugees left behind at the Houei Nam Khao camp in Thailand, subject to many issues brought up by the Thai and Lao armies as part of their negotiations to get the refugees sent back to the Laos PDR. Of all refugees that came to Thailand, the Hmong were the ones that suffered the most. All of them were sent back to Laos PDR on December 28, 2009, more specifically to Ban Phone Thong, Borikhamsay Province.

Notes: Civil servants, military officers and highly educated leaders mostly ended up in France because of the more relaxed entry requirements used by the French Government in 1975. The US waited until 1976 to accept Lao refugees in the USA, claiming that there was still a US Embassy in Laos. They also only picked selected group of refugees, i.e., those working for USAID and/or serving as interpreters. The US Christians were next in welcoming Lao Christians into the USA. The last group that was admitted consisted of military officers, and soldiers and their families who were fighting in the Vietnam War on the US side. This explained the high number of military members among the Lao refugee population in the USA. Many Americans still consider the Hmong as stone-age people because of the long war in Laos.

Notes from Col. Vang Neng, Head of Ban Vinay Refugee Camp

Col. Vang Neng started serving as representative of the Soune Vinay’s refugees in September 1979, replacing Col. Vang Yi who left for a third country (USA). This was a difficult and dangerous time as a result of the transfer of refugees from the Nong Khay and Nam Fong camps into the Soune Vinay camp. The Soune Vinay camp, which was originally created to accommodate only 12,000 refugees, then had to shelter 42,000 refugees. Because of the influx of refugees, the refugee camp was subdivided into seven zones, each headed by a representative lead and a management team. Zone 5 was originally reserved for lowland Lao refugees. Before long, conflicts soon surfaced between the lowland and the highland Lao refugees, created by misunderstanding from among the younger refugees. The camp management realized that the misunderstanding came from differences in customs and languages; it then moved Zone 5 refugees to the Na Pho camp, leaving Zone 5 facilities practically empty.

Despite that move, problems still lingered because of the presence of many ethnic groups, including friends, foes, and ill-intentioned elements. Drug trafficking and other illegal activities created bad reputation and insecurity, and led to the daily arrest of wrong-doers. Robberies and nighttime murders became alarming and very scary. Col. Vang Neng then decided to lay out protective plans for the camp to ensure its existence, including several committees: Central Committee, Zone Committees, Neighborhood Committees, and Building Committees. One building accommodated several families. The performance by each committee was not fully satisfactory because of the uncertainty surrounding the departure to third countries. Conflict resolution was also hard to perform and did not meet the need. As a result, changes were deemed necessary. Also, a request was submitted to the United Nations for funds to build work offices at Ban Vinay for the following officials/offices:

- President or Refugee representative

- Two vice-Presidents, and Secretary Team; financial committee; audit committee; committee in charge of arrivals, departures, birth, death; youth committees, and security committee.

The duties of the Central Committee were as follows:

- Managing and solving problems of all the refugees in the camp

- Contacting the Thai authorities and the refugees organizations

- Developing security plan including security guards for every building

- Contacting all religious and assistance organizations to seek help for the refugees

- Developing plans for education, health, profession, and future career

- Scheduling workshops to promote mutual understanding and orderly co-existence

- Reviewing individual plans to resettle in a third country, and following up with refugees who have already left the refugee camp, and

- Resolving miscellaneous issues in the refugee camp.

Photo #177. Col. Vang Neng opened the ceremony of Hmong New Year 1979 at the refugee Camp at Ban Vinai. The first two persons behind him to his left were Maj. Vue Mai (who became the Camp Representative after Col. Vang Neng went to the US in 1984). Standing furtherto the left was Neng Lo Yang. In 1992 the Camp was closed. Vue Mai led some Hmong back to Laos and about three years later, completely disappeared from public view.

The Clans Committee had the following duties involving the 18 Hmong Clans (Vang, Yang, Lee, Xiong, Heu, Mua, Khang, Kong, Thao, Pha, Thang, Vue, Lo, Tsheej etc. :

- Serving as the clan’s elder with full authority to resolve issues within the clan

- Serving as member of the Central Committee as a representative of the clan

- Resolving all the internal issues of the clan

- Addressing wedding-related issues affecting members of the two clans involved

- Helping in conflict resolution affecting other clans as requested

Photo #178 Col. Vang Neng, refugee representative at the Ban Vinay Camp making a speech at a preparatory meeting in 1980, asking all his fellow refugees from Laos to care for each other during difficult and hopeless times.

The Inspection Committee had very important tasks to perform such as:

- Inspecting all suspicious buildings and facilities and reporting back to the Central Committee

- Monitoring the behavior of the members of the Central Committee and various developments within the camp

- Tracking the performance of the Clans Committee to ensure fairness and equity

The Advisory Committee provided opinions on various issues that are affecting or are likely to affect the refugee camp. Members of this Committee were hand-picked by Col. Vang Neng from former members of the military, police, civil service and educated and experienced elite groups to develop plan and/or resolve issues. After forming this committee, Col. Vang Neng held a meeting to address the following three issues:

- Refugee arrival and departure

- Security surveillance and change of guards at each building

- Ensuring the security of the refugees

Col. Vang Neng explained, “We are refugees living in another country. Our lives have changed. We do not have the same freedom to do what we want to do as we did in Laos. If anyone breaks the rule, he/she should be punished according to the laws of the host country. We refugees have no special rights; we can only use our eyes to look. We must find ways to communicate so we can co-exist and understand each other as a group and survive until we reach the following two scenarios: go to a third country or return to Laos. The one who has the right to live in Thailand is only the one with the Thai nationality. Even the refugees’ children who are born in a refugee camp are treated as foreigner –not as Thai citizens.”

Once everybody knows that we refugees only have two options, we need to think and decide which of the two options to choose — go to a third country or go back to Laos. Or, remain hopelessly in the refugee camp? Because of this, everyone needs to plan ahead and be ready, especially the young fellows. You must go to school, learn a profession, learn dancing and perform various sport and Hmong cultural activities, so you can take advantage of later when there is an opportunity to do so. Everybody has to be self-conscious and improve himself/herself before it’s too late.”

After Col. Vang Neng’s speech, many asked questions and cried, because most of them were not educated and only fought under their leaders’ orders. Without orders, they did not know the way out.

Furthermore, many religions were practiced in the refugee camps and made it difficult for people to understand each other and maintain a smooth relationship. I had the chance to explain to everybody that religion is their own choice. They may believe in any religion but should not impose their religious belief on others or associate that belief with human co-existence, public administration, or refugee organizations. They should keep it within their family or within their religious group. Our internal cooperation is another item that will benefit from foreign assistance. Internal conflict and mutal disputes in refugee organizations were the source of disunion and unproductive, damaging, and self-destructive results. Everybody should join hands to show their sincerity, openness, and cooperation, and achieve progress and security.

After the meeting, the committee activities, security inspection and surveillance resulted in a surprisingly high drop in assassinations, robberies and drug-trafficking. Everybody loved and understood his/her neighbors and was willing to do everything possible for the collective good in the refugee camp. All the problems were abated by almost 100 percent –a real accomplishment for the Soune Vinay’s refugees. This corresponded to the appointment of the new Thai Refugee Camp Manager, Bandit Omthaisong –a highly-educated, generous, and skilled manager who liked to lean on the majority rule as a basis for decision-making. In order to enhance the refugees’ unity, Mr. Bandith worked closely with Refugee Leader Vang Neng, often asking him about the various Lao events that created so many refugees. This used to be a topic of high interest to Thailand, a neighbor country to Laos.

Mr. Bandit did not only take care of the refugees, but he also invited the new Chanwad Governor Thongdam Banexung, the security chief, and the police officials to visit the refugees during the Hmong New-Year celebration (Kinh Chiang). On this occasion, Col. Vang Neng expressed his thanks to the King of Thailand, the Thai government, and the Thai people for allowing the Lao refugees to stay in their country. He talked in detail about the various actions that the Lao Communists –the protégés of the North-Vietnamese– did to violate signed agreements, divide the Lao people, bring the Vietnamese communists in to fight the Vientiane faction and force them to flee abroad. He also mentioned about potential impacts to Thailand, because the Vietnamese communists were eager to expand their influence to the rest of southeast-Asia.

Col. Vang Neng’s speech, made in 1979, convinced many Thai leaders to organize workshops to discuss the various events within their communities. They invited Col. Vang Neng to provide a briefing on the Lao historical events, including the violent communist tactics used against the Vientiane faction. The briefing was of great interest to the Director-General of the Thai Ministry of the Interior and the Director of the Thai Army’s Psychological Operations Department Director who came for a visit to the Soune Vinay camp. Later on, the Thai Minister of the Interior himself made the trip, followed by over 100 deputy-governors, then all the Thai governors led by the Governor of Bangkok. The whole purpose for those site visits was to learn about the various events that took place in Laos in order to develop the proper defense plan for a country that was the next logical communist target in southeast-Asia.

Vang Neng clearly explained that the refugees asked for permission to stay in Thailand for some time waiting for the situation to improve in Laos. If possible, some of them would return to Laos, others would continue to go to a third country; those born in Thai refugee camps would keep their refugee status and not try to get Thai citizenship. When the provincial governors heard that statement, they felt pleased and applauded the speaker. Col. Vang Neng also added that regardless of how difficult life in refugee camps was, refugees had to try to be patient and wait for a chance to either go back to their country or go to a third country to restart a new and free life. The Thai governors were pleased with that statement as well. Those meetings helped strengthen the understanding of the governors and other officials of the refugee issue. Later on, officials from Chanwad Leui were invited to participate in sport events at the refugee camp. They then returned the favor and invited refugees to participate in a parade and sport competitions with the people of Chanwad Leui.

Survey of Hmong Refugees on Their Plan and Vision

The results of the survey revealed that most of the older and elder refugees would like to go back to their country of birth. Most of the young people, with some education and less than 45 years old, would like to go to a third country to start a new life, and not to go back to live a dangerous life under a communist regime that limits their freedom. As for Col. Vang Neng, who spoke as refugees’ representative and had learned many good lessons, what he remembered most vividly was the fact that highland Lao Hmong wished to have open-minded leaders with a good leadership plan, a decision-making process based on majority count, and adequate home-work before execution time. They did not want leaders who only relied on their power, were only interested in money, and only worked for their party associates. Instead, they wanted to work with, for, and under transparent leaders. Therefore, future Lao and Hmong leaders will have to train themselves very hard, get a good education in many fields, and build a good reputation.

In 1984, conflicts started to rise again at the Soune Vinay refugee camp as a result of the change in the Thai policy to get closer to the Laos PDR policy on border control regulation. Many inter-related and complicated issues forced many refugees to leave for a third country. Col. Vang Neng himself had no choice but to leave the refugee camp, because Thailand had opened the door for too much communist interference in Thailand.

Closure of Refugee Camps

Namphong and Nongkhai Refugee Camps, which were closed at the same time in 1976, transferred all their refugee population to the Vinai Refugee Camp. Soune Vinay itself also was closed in 1992 as a result of the change in policies between Thailand and Laos PDR. Several thousands of Hmong refugees were transferred from Vinay Camp to Na Pho Camp to undergo physical examinations and complete the paper work needed for transfer to a third country.

Notes. The closure of the Vinai Refugee Camp in 1992 resulted from the figth between Thai and Laos PDR armed forces around three villages along the Laos-Thailand border. Thailand lost those three villages to the Laos PDR in 1984. On December 12, 1987 and January 1, 1988 the fighting broke up again on Phousone Say Loumkao Mountain. Thai troops launched many successive attacks but were not able to make any head ways. They then rounded up several Hmong living in Thailand and Hmong refugees in Thai refugee camps to fight with them, and this time met with success. Lao PDR troops were about to mount counter-attacks when Thailand threatened to recruit more Hmong refugees to do the fighting, compelling the Laos PDR to stop the attacks and to offer to negotiate without pre-conditions.

The negotiations led to the closure of all the refugee camps in Thailand, including Soune Vinay Camp. Several thousand of Hmong refugees who did not wish to go to a third country went into hiding in the caves of Thamm Kabork under the care and protection of Headmonk Louang Pho Khouba. When the headmonk died in 2006, this camp was also closed. Thousands of refugees then moved to a third country, although a group of about 7,000 refugees went into hiding at the Ban Houei Nam Khao in 2007.

In 2006, the Thai authorities dug up the bodies of Hmong refugees who died during an armed ambush and were buried at the Thamm Kabork camp –about 500 of them. One of the bodies belonging to a woman who died almost a year ago looked still fairly fresh as if the woman had just died a few days ago. Later on, friends and relatives of the deceased Hmong wondered where those bodies were moved to. The Hmong living in the USA demanded answers to the same question, but to no avail because we were just immigrants who came here to ask for shelter.